(Bear with me. This tale takes some telling.) You might reasonably assume that my initiation into the world of satire occurred well before my 25th year, but you’d be wrong. I’ve written in this space before that I really didn’t start to read fiction until my late twenties. Back then, I was more focused on my political career in the crucible of Parliament Hill, so I was reading nonfiction in general, and economics, political science, public policy, biography, and history in particular. Though, I was starting to thinking about writing. While working in Ottawa, starting in 1984, I wrote a couple of short stories. I didn’t send them anywhere or tell anyone about them, but in hindsight, it seems I was taking my first faltering steps as a writer. I was writing purely recreationally—and not very well—and my stories were utterly devoid of humour. But I was enjoying the process, though my output was scant.

In January of 1985 I was working on Parliament Hill for a Liberal MP when I miraculously found myself invited to visit Strasbourg, France, as the sole Canadian delegate to a conference put on by the International Federation of Liberal and Radical Youth (IFLRY). Surely you’ve heard of them. No?

Yes, there is such an organization, founded in the 1920s, with European and Scandinavian countries comprising the lion’s share of the membership. The Young Liberals of Canada remain a full member of IFLRY today as they were when I was lucky enough to be chosen to represent the youth wing of the party back in early 1985. When writing this post, I did note, while perusing IFLRY’s website, that they have dropped the “Radical” from their name, but to appease certain factions they have kept the “R” in the IFLRY acronym. Confusing? Perhaps. A negotiated compromise? Almost certainly. But I digress.

It was at this IFLRY conference on Racism and Xenophobia in Strasbourg that for the first time, I understood the meaning and power of satire, courtesy of these two unlikely friends: Stephen Biko and Donald Woods.

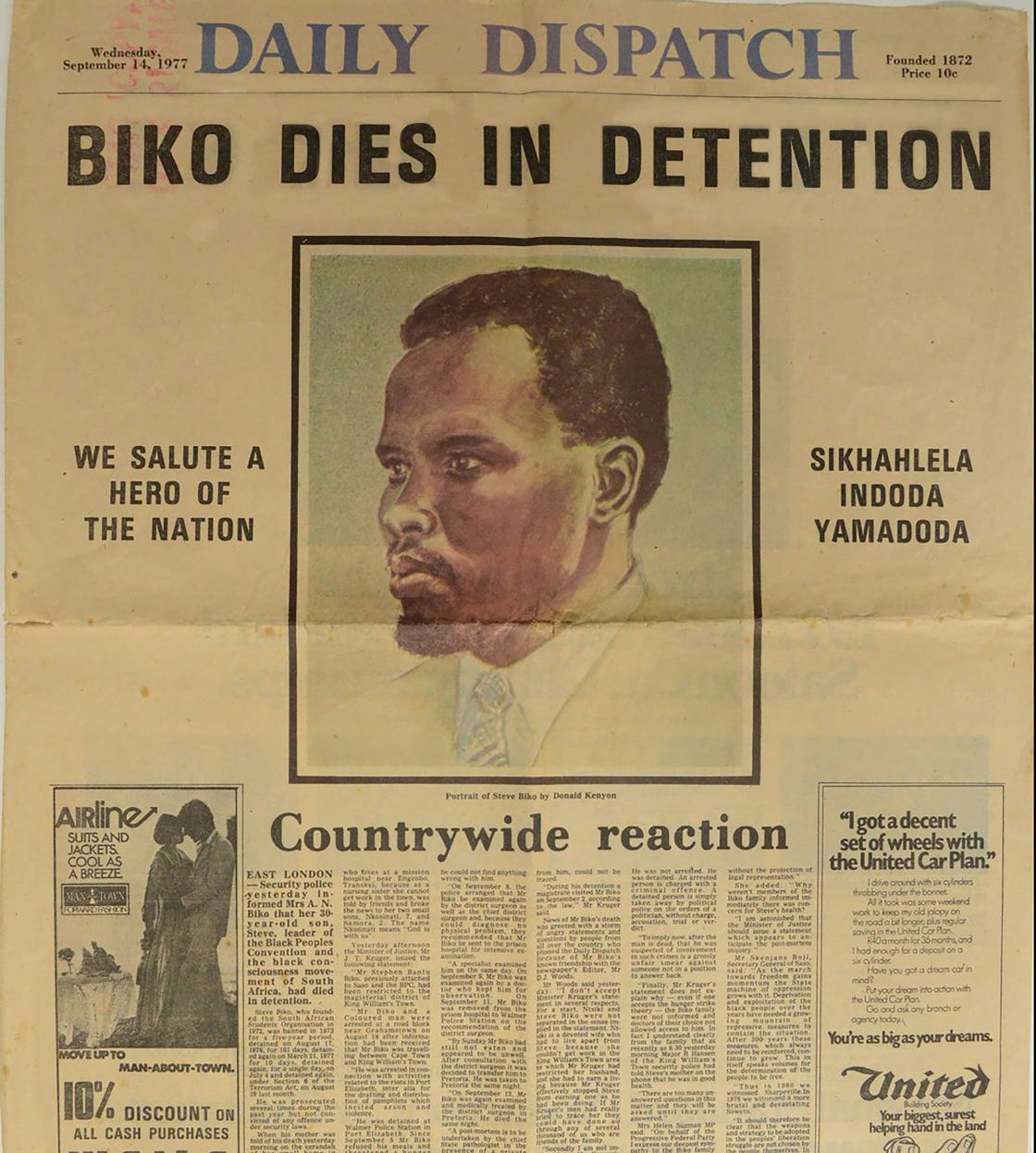

Stephen Biko was the founder of the Black Consciousness movement and a leading anti-apartheid activist in South Africa. Donald Woods was the editor of The Daily Dispatch in South Africa’s Eastern Cape.

Neither are still with us, but it was the death of Stephen Biko in 1977 that changed—and ultimately threatened—Donald Wood’s life and eventually brought him to that European Youth Centre in Strasbourg in January 1985. As I recall, there were about forty young delegates from all cross Europe and Scandinavia. There was one American delegate and one Canadian (moi) rounding out the contingent. Now, for this story to be meaningful, I need to provide some context for what happened in Strasbourg.

A bit of background

At the time, and right up to the release of Nelson Mandela and his subsequent election as President in 1994, apartheid was alive and well in South Africa—or maybe “alive and evil” is a more apt description. Black South Africans could not vote, could not marry outside of their race, were forced to live in designated townships where poverty, unemployment, and substandard housing were just a part of daily life. Apartheid was driven by a government legislated racial classification system that oppressed all those who were not white. Stephen Biko was a thoughtful, committed, and charismatic leader of the anti-apartheid movement and was gaining national prominence and support among those excluded from equal participation in South African Society—who, by the way, constituted the majority of the population.

Donald Woods was the editor of a leading daily newspaper in the Eastern Cape of South Africa and was introduced to Biko. They became unlikely friends as Donald Woods, over time, became a convert to the anti-apartheid cause.

In September of 1977, Stephen Biko was arrested and beaten to death in police custody. A photo of Biko’s battered body was smuggled out of the jail. Donald Woods bravely put the atrocity on the front page of his newspaper, including a prominent headline: “We salute a hero of the nation.”

The government was not happy with the coverage and responded quickly, banning Donald Woods from the country in which he was born. Justly fearing for his life, Donald Woods dyed his hair black, disguised himself as a priest, and managed to slip across the border to Lesotho. He was eventually granted asylum in the UK where his wife and children joined him shortly thereafter, to live in exile. Donald Woods continued to criticize the apartheid regime from London and became a very vocal and sharp thorn in the side of the internationally reviled South African government. Okay, sorry for the history lesson, but it’s important context for my epiphany in Strasbourg, some eight years later.

So what happened in Strasbourg?

None of us had heard of Donald Woods before he stood at a the lectern in Strasbourg that January afternoon in 1985. We young liberals were appalled and angered by apartheid and had just spent the morning pasting “Non au racism” stickers on telephone poles in the city. We were primed to listen to Donald Woods and learn about the horrors of apartheid. He was introduced and began to speak. Within about thirty seconds every single one of us in the room was laughing hysterically. I’m not kidding. Woods described just how ludicrous and bizarre the South African “pass book” laws were that gave force to the racial classification, all based on skin pigment. While we knew how discriminatory, malevolent, and violent the regime was, the way Woods described it had us all splitting our sides in gales of guffaws. I distinctly remember thinking to myself as the tears of laughter streamed down my face that I should not be laughing about apartheid. It was not a laughing matter.

That afternoon, Donald Woods taught me a lesson I’ve never forgotten. He helped me to understand that we weren’t laughing “about” apartheid, we were laughing “at” apartheid. And when you laugh at something, you weaken it. In his talk to that group of young liberals nearly forty years ago, Donald Woods was satirizing apartheid, and the penny dropped.

Satire takes aim at the status quo, unbridled power—in this case, institutional discrimination and legislated racism—and uses humour to undermine its authority. My simple definition is that satire ought to make us laugh AND think. (If the words only make us laugh, they’re likely just funny, and not satirical.) Donald Woods opened my eyes to satire. He had a very specific target and he attacked it relentlessly using satire, a weapon we employ too sparingly in my mind.

Hollywood?

Back in Strasbourg, the American delegate and I stayed up most of that night playing billiards with Donald Woods and talking. (Somewhere, I have a photograph of us in the games room together, pool cues in hand. But I just can’t find it and it’s driving me nuts.) Woods was a great guy, truly committed to his cause. At one point in the wee hours of the morning, he mentioned that Richard Attenborough was directing a film about his dramatic break with the government of his own country. The movie was based on his 1978 book, Biko. I confess, I didn’t give it much thought at the time, yet a couple of years later, in November of 1987, I went to see Attenborough’s great film Cry Freedom. Denzel Washington played Stephen Biko and Kevin Cline played Donald Woods.

A film well worth revisiting for a look inside the apartheid regime.

But what does it all mean?

To me, satire gives us a different—and sometimes more effective—entry point to consider important social justice issues. The standard MO of social movements is, understandably and justifiably, outrage and anger. I saw it every day on Parliament Hill when I worked there. That’s right, every day a different protest rally convened on the lawns of Centre Block—sometimes there was a demonstration in the morning and a different one in the afternoon. Angry chants constantly echoed across Parliament Hill. Every day it was a different movement, a different and worthy social cause. But over time, the impact on the public—let alone government—of these angry demonstrations declined through repetition. Passers by—and more importantly, the parliamentarians in the House of Commons just a stone’s throw away—stopped listening. On my walks to and from my office, I could hear the angry chants, but—and I’m embarrassed to admit—I often didn’t know what they were saying or what they were protesting. It just happened so often, and eventually just washed over me as I hurried by. It’s a very human response to tune it out after a while.

So giving citizens a different route into the issue—like satire, for instance—may in fact be a more effective recruitment strategy. Get them laughing and thinking at the same time. Bring them into the tent with humour and you may gain more converts and supporters than with the more traditional rage and anger—again, not that rage and anger aren’t wholly justified. I also think that using humour to introduce people to important social causes and make your case, demonstrates confidence, a commodity all movements need.

Full circle

I was thinking of Donald Woods as I wrote The Best Laid Plans some 20 years after my trip to Strasbourg. In fact, the roots of my first two novels can be traced directly back to that youth centre in Strasbourg all those years ago. As I’ve written before, my debut novel was about more than just making readers laugh. Of course, some readers will simply enjoy the funny story—and I’m fine with that—but I hope others will give passing thought to the more serious issues that lie beneath the humour. I really wanted readers to think about the state of politics and the steps we need to take to restore public confidence in our democratic institutions. I wanted them to recognize, consider, and support the different approach Angus McLintock pursued in his foray into politics—you know, putting the nation and the public interest first, sometimes even at the expense of political self-interest. Needless to say, I wanted them to laugh and enjoy the story, too.

Satire may seem to some to be trivializing important issues. But I think satire, when wielded skillfully, can be a very trenchant instrument of social comment and perhaps more effectively introduce readers—or more to the point, citizens—to important issues they might not otherwise have considered. Even if not every reader picks up on it, humour can be a vehicle for education, advocacy, and even change. That’s what Donald Woods taught me back in 1985 in a small city in eastern France.

Thanks for dropping by. Next week? Who knows, but I’ll be back. Hope you’ll subscribe and share if you haven’t already. Many thanks.

This might be your best yet. You absolutely nailed it (i.e. the power of satirical writing). When are you writing a book on the subject??

An excellent column, Terry. It strikes me as essential that more Canadians (and certainly the rest of the world-especially Americans and the fellow who once was President) need a primer on satire..