I often wonder how writers are formed. What shaped their approach to writing? Why did they even consider writing in the first place? What, or who, do you find when you trace a writer’s path back to their roots? Interesting questions. When I examine—perhaps exhume—my earliest influences that, decades later, would lead me to the writing life, I know who I’ll find…

Meet my father

Now, don’t misunderstand me. I suspect my mother had just as much influence—perhaps even more—over how I turned out as a person, but this post is about tracing the roots of my life as a writer. It’s not a competition, but in hindsight, I think it was more my father who set me on this path.

His story in brief

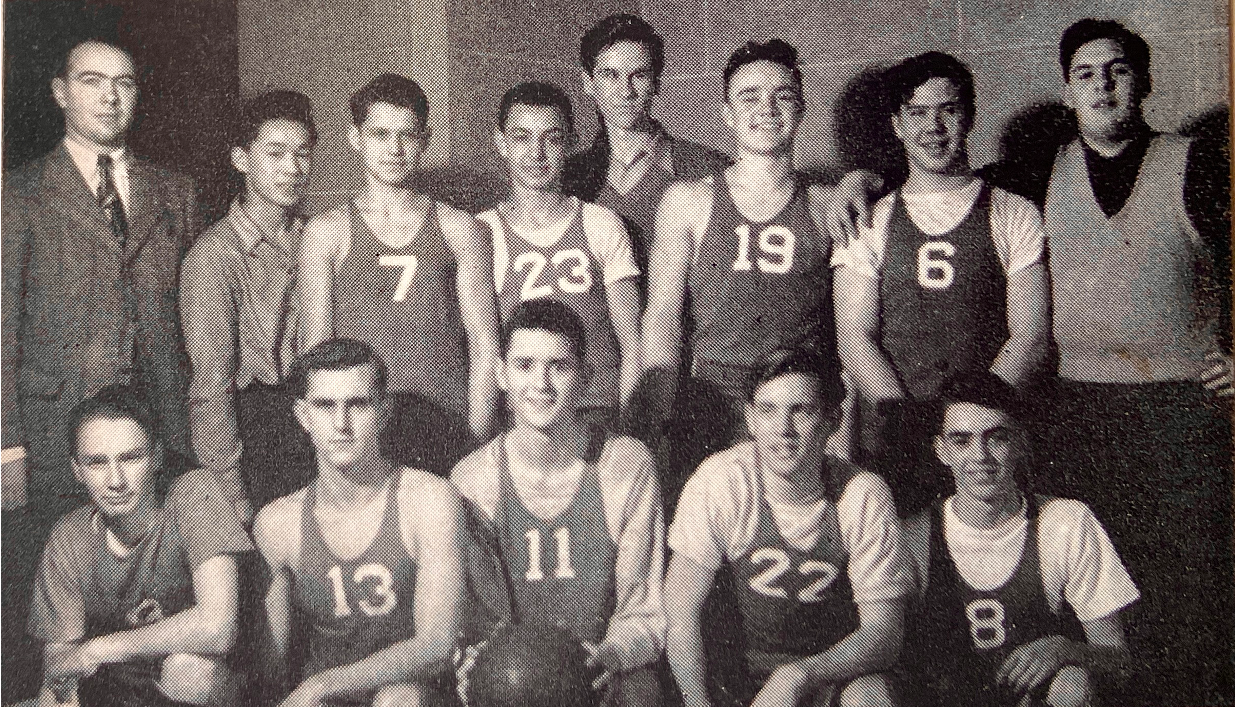

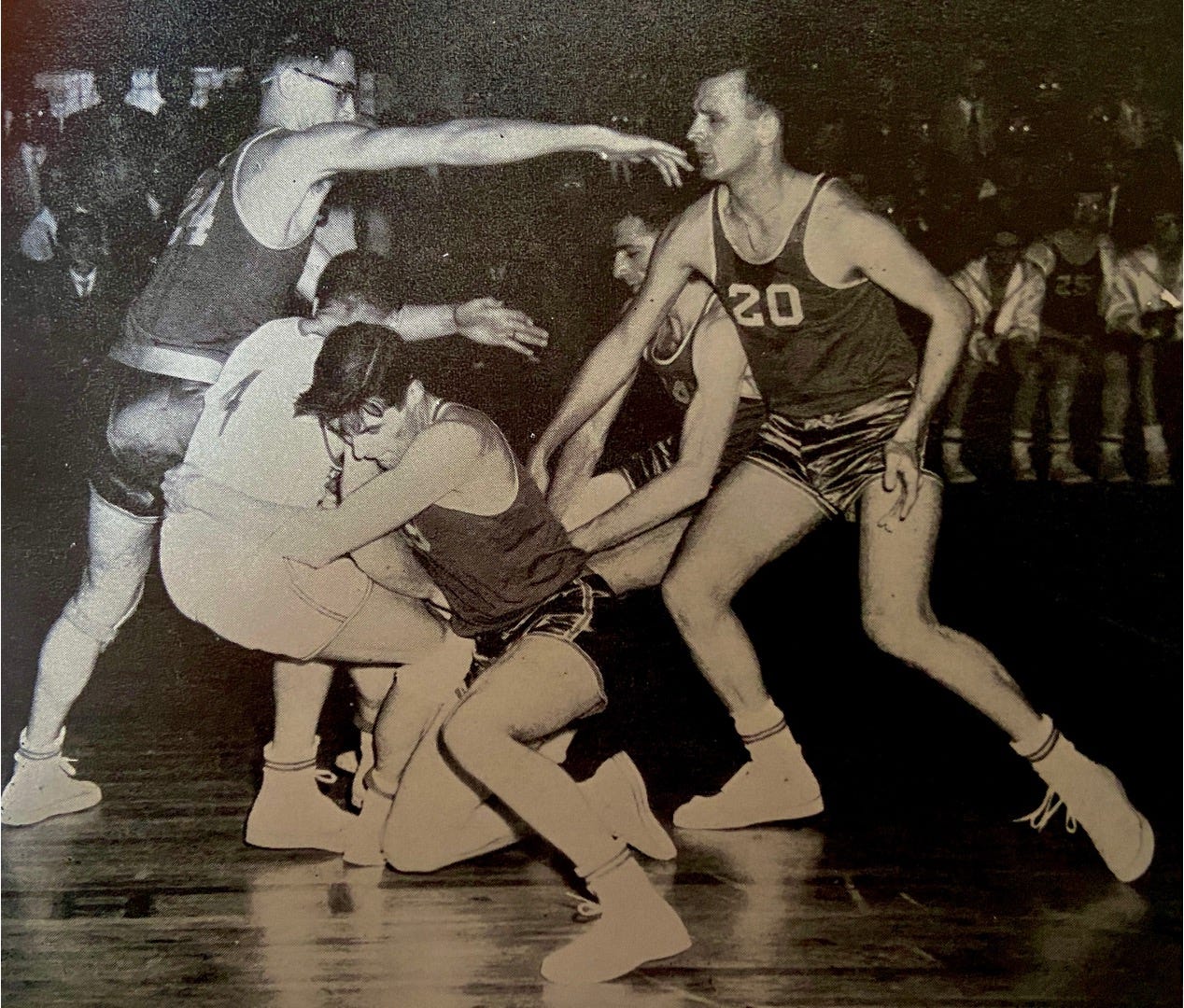

Jim Fallis, my father, was born in the spring of 1929 in London, Ontario. He passed away early in 2019 in Clearwater, Florida in his 90th year. He was very tall, even as a young boy, and topped out at six foot six. As his bodily altitude might suggest, basketball was his game. He played in high school, at the University of Toronto for the varsity team, and at West End Y—aptly named for it was in the west end of Toronto—where he also coached a ragtag, underdog juvenile team to an unlikely national championship.

My father earned what was then called a Bachelor of Arts in Physiology from the University of Toronto before heading to medical school. He became quite a prominent pediatric surgeon at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children (colloquially known as “Sick Kids”). His second act was as head of Pediatric Surgery at North York General Hospital when it opened in 1968. In the late seventies he returned to Sick Kids as the first Director of the Emergency Department, and was also instrumental in launching Ontario’s then fledgling air ambulance service.

That’s a quick overview of his career, but for obvious reasons, his influence on me was more related to who he was at home. At least some of my father’s writerly inclinations seemed to have rubbed off on me, even if they took a while to manifest.

A love of language

Perhaps first and foremost, my father loved words and language. He was raised in a home that revered English and its proper usage, and he passed that love along to me. And he was certainly a stickler for proper grammar. He would never let any of his kids get away with a grammatical indiscretion, or the improper use of a word, or, really, any offence against the language, be it minor or massive. Yes, he was that guy. But he always framed it in a way that enhanced our respect for the language rather than leaving us annoyed or resentful.

We would sit around the Sunday evening dinner table debating the geopolitical implications of the split infinitive—it did cut down on dinner guests. Okay, I exaggerate, but only slightly.

My dad was also a writer, though he stuck to his profession and stayed in the nonfiction lane. He wrote several books about surgery, emergency medicine, and the treatment of the injured child. As a veteran summer camp physician, he also wrote a more personal guidebook of sorts for camp doctors. He enjoyed the writing process, and you can be sure, there were no grammatical transgressions in his manuscripts!

Thanks to my father, what I remember well from my teenage years was a dawning realization that the richness and diversity of the English language offered nearly endless creative possibilities, among them of course, storytelling. But I would wait nearly thirty years before writing my first novel.

Sense of humour

My father was funny… very funny. Whether at home, out with friends, or in the Operating Room, his wit was usually on full display. He had a very dry sense of humour—parched, in fact—and was quick with the one-liners. But he also enjoyed wordplay and could pun with the best of them. When I’m on the road giving talks and readings and workshops, I continually meet readers who worked with, or were operated on by, or somehow met, my father. After noting how tall he was, his sense of humour was usually the next memory conveyed.

My father also had a very high laughter threshold. Making him laugh at the dinner table felt like a Herculean achievement. My twin brother Tim and I would compete to try to make him laugh. It didn’t happen often, but he did have a “tell” when he was getting close to cracking up. A small muscle just below his left cheekbone would start to quiver ever so slightly when his resistance was running low. When we picked up on this, Tim and I would turn up the humour heat knowing we were close. Eventually, Dad would surrender and collapse in laughter. It made you feel like you’d just won the Leacock Medal for Humour.

Whatever sense of humour I now have and bring to bear in my novels, I gained growing up in a family where laughter was a daily phenomenon, with my father usually at the centre of it.

Curiosity

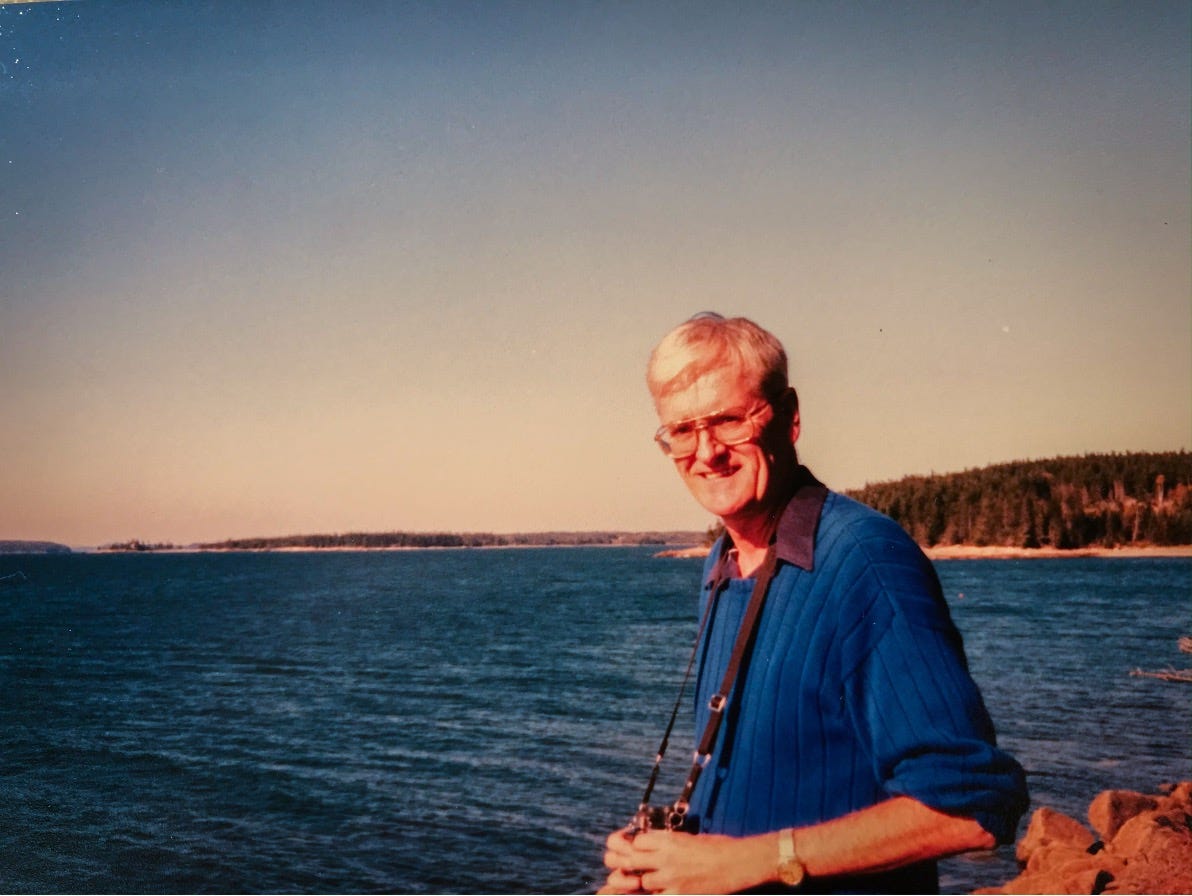

My father had an active mind, a curious mind. I’ve always considered curiosity to be a writer’s greatest gift. (I wrote a post about curiosity a year or so ago and you can read it here.) Dad was interested in many things, sports, leadership, and medicine (obviously) among them. Later in his life, he and my mother became interested in, excited about, some might even say obsessed with, bird watching. They made many trips within Canada and internationally to indulge this passion for ornithology. On their annual birding weekends to Point Pelee, they would occasionally see Margaret Atwood out early in the morning with her binoculars. In many photos of my father, particularly at the family cottage (like the one that opens this post), you’ll see binoculars hanging from his neck. He was always ready.

So it’s quite possible that my father’s varied interests boosted my own sense of curiosity. Without it, I doubt I’d have written nine novels with a tenth on the way.

A methodological approach to problem-solving

My father was definitely a man of science. He could talk physics, math, and chemistry for a very long time—I know, I was there. But I think this academic orientation also engendered a methodological and analytical approach to problem-solving, whether it was figuring out why the barbecue rotisserie motor had failed, free-styling the design and construction of a deck at our cottage, or reacting to an emergency situation during surgery. In short, he leaned on the scientific method to sort through challenges that weren’t always strictly scientific in nature. What are the knowns? What are the unknowns? What can I control? What is beyond my influence? Etc. etc.

My decision to study engineering also left me with a certain engineering framework within which I tackle issues that have arisen in my own life. You can see this approach in how I map out my novels in a very detailed fashion before finally writing them. In short, I engineer a detailed blueprint of my novels long before I write them. My father told me that he relied heavily on outlining when writing his books. I strongly suspect my scientific inclination and methodological approach may have come from my father. Like father, like son.

Wrapping up…

I often wonder whether I’d have ever become a comic novelist had I not grown up in a family that revered our language and spent a good chunk of each day laughing with one another. It’s probably not quite as straight forward as that, but I see several parallels in how my father approached life and all its challenges, and how I have—so far, anyway. I look back on the contributions both of my parents made to my development with deep gratitude. I miss them both. Would I still be a writer today without them? Who really knows?

Thanks for checking this out. I hope you’ll consider subscribing and sharing. It’s free and easy. See you in two weeks.

Your tribute had me in tears Terry. Your Dad, my Uncle Jim, had a great influence on all of us who bear the Fallis name. I remember well those Sunday night dinners when one was careful not to err in our conversation. It must have run deep in the family prior to our generation because my Dad and our Nana had many of the same characteristics. We are all better people because of the influence of your Mom and Dad and indeed our Fallis heritage. 🤗🥰

What a wonderful tribute to your dad. My family's interaction was very different, however, my father, also, was the one with a quirky sense of humor. Mom would roll her eyes at him dramatically.

I soaked-up that affinity for humor and it has served me well while dealing with mom's slide down the dementia rabbit-hole in recent years. Note: she still rolls her eyes!

Thanks for sharing your father's remarkable life and influence.