The engineer inside the writer?

Writing Life: 17

I don’t spend much time talking about it so it’s perhaps not surprising that many of those who have read my novels—perhaps most—don’t know that I have a Bachelor of Engineering (Mechanical with a focus on biomedical) from McMaster University. I suspect the majority of impartial observers out there would consider an engineer to be about as different from a novelist as you can get. Engineering is rooted in math and science, laws, theorems, facts, and is generally not known for yielding brilliant communicators. On the other hand, creative writing is, well, creative, artistic, “made up,” and driven by the ancient art of storytelling. Now, to be clear, I’ve never formally practiced engineering—not for one instant in my life. I left McMaster as a newly minted engineer and immediately started my early career in federal politics before eventually moving to the provincial level. But I’ve come to believe that the engineering side of my life has had a significant influence on my writing life, perhaps even the single most significant influence. Let me start at the beginning.

Early days

Growing up, I was fascinated by things mechanical, particularly if they flew or at least were fast. So I loved engines, go-karts, cars, planes, rockets, helicopters, gliders, hydrofoils, hovercrafts, and various other devices, inventions, and contraptions. My early primary school notebooks were filled with doodles of aircraft and automobiles and rockets. I once spent all the babysitting money I’d saved on a working model of a V-8 engine that I had to build myself, with pistons that moved up and down, valves that opened and closed, and spark plugs that lit up in the right sequence. (Yes, I know. I had an exciting childhood.) I also collected books about my interests and obsessions and still have many of them.

I still know nearly every dog-eared page and photograph in those books. They fuelled and shaped my life-long interest in aviation, space, and mechanics in general.

One of my heroes is Alexander Graham Bell, mostly because of the breadth of his interests. Most know him as the inventor of the telephone, but frankly, that’s the achievement that interests me least. I was much more excited by his record-breaking hydrofoil and his experiments with kites and flying machines. He was a polymath of the first order, and that’s what made him fascinating to me. And he took his interests beyond the drawing board. He actually built things to understand how they worked.

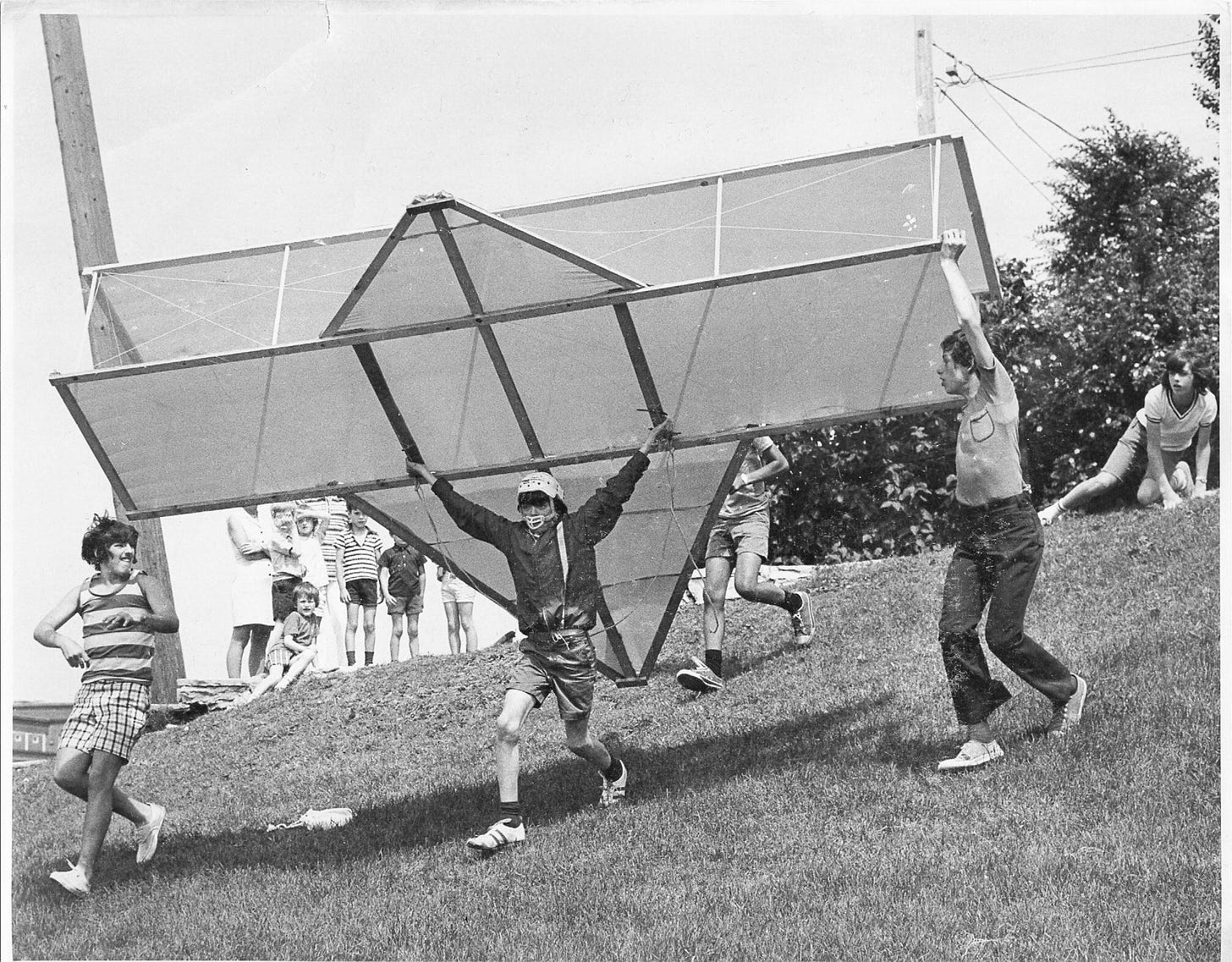

This rubbed off on me as a kid. I didn’t just draw pictures of flying machines, a classmate and I designed and built a few, too. In fact, we designed, built, and tested three hang gliders—the Falcon Series—and a full-sized hovercraft—the GTH1, which of course stood for Geoff (my co-conspirator) and Terry Hovercraft 1. Everything needs a cool name, right? Needless to say, the hang gliders were not exactly air worthy and didn’t quite get off the ground. But the hovercraft worked very well.

So engineering seemed like the logical course of study for me to pursue when I set off for McMaster University in 1978. Man, it was a tough grind, particularly in hindsight when it became clear that my fascination with other career paths (e.g. politics, public affairs consulting, etc.) overtook my interest in engineering.

I think I knew by the time I was in third year that after graduation I was going to try my hand as a political staffer on Parliament Hill rather than head into engineering as a career. But when you’ve made it through three years of an engineering degree, you bloody well finish it. And so I did, and have never had a moment’s regret.

Engineering’s connection to my writing

Let me return to my aforementioned contention that my engineering experience has profoundly influenced my writing life. While the two worlds—engineering and writing—seem wildly disparate, I’ve decided there are many crossover benefits.

Discipline

I was not a gifted student. Any modest academic success I achieved at university—and by modest I mean that I graduated in the top three-quarters of my class—was simply due to buckling down and getting the work done. At times it was like drinking from a fire hose. In short, given its demanding course load, earning an engineering degree requires discipline. You either started that fluid mechanics assignment the very day you got it or you simply wouldn’t get it done in time to meet the deadline, given the other assignments, tests, readings, and projects crowding your plate. Those who weren’t disciplined in their approach to their heavy weekly work load usually didn’t make it out of first year. As I recall, there were over 500 first year engineers at Mac in 1978 and only about 200 who made it through to second year. I felt lucky to make it.

Discipline is often among a successful writer’s greatest assets. The ability to hunker down—even when you don’t much feel like writing—and put your ass in the chair and your fingers on the keyboard is critical to creating and refining a 100,000 word manuscript within a reasonable timeframe. I credit the demands of my engineering education for entrenching a strong work ethic and inculcating the disciplined approach I like to think has contributed to my modest success as a writer. Was that discipline there before my McMaster years? Perhaps, but I think it really took root at university.

Curiosity and creativity

I won’t dwell on curiosity here as I’ve written a stand alone post about how important it is to most writers. But I don’t know very many engineers who aren’t driven, at least in part, by curiosity. They have a need to figure out why something behaves the way it does—metal components under compression, aircraft in a cross wind, rubber tires in low temperatures, buildings during an earthquake, etc.—and what can be changed to improve performance. Alexander Graham Bell’s curiosity was legendary across a broad diversity of fields. And it really comes to life when his curiosity is complemented by the creativity—not to mention gumption—required to fill a need, solve a problem, or meet a challenge. I like to think my engineer’s curiosity—and I hope creativity, too—is alive and well in my novels.

Planning

As I’ve often said, engineers don't build a bridge without a blueprint, and I don’t write novels without one either. It’s just how engineers think. They measure twice and cut once. They are not designing and building an electric car by the seat of their pants. They plan it all out and test their theories and designs before they ever start building. That’s exactly how I write my novels. I need to know my story—and that it works—from start to finish, the highs the lows, the action, the foreshadowing and resolving, all before I ever write the first word in the manuscript. Part of this is the engineer’s innate interest in efficiency. Engineers want the most direct path from idea to prototype to production—or for the novelist, idea to manuscript to published book. That’s how I think, too, though discovering and developing the way that one writes best is a deeply personal journey. So I make no judgements about those who write with or without outlines. I just know that I can’t write at my best without a detailed scene-by-scene plan, often running at more than 90 pages, to guide me in eventually writing my manuscript. That personal writing imperative has its roots, I believe, in my engineering inclination and education.

Methodological approach to problem-solving

Engineers tend to take a logical and well-reasoned approach to problem-solving. In essence, it’s the scientific method brought to life. You know, it starts with a question, followed by research and the development of hypotheses. Then there’s testing and analysis followed by refining or rejecting solutions. I find I apply the same approach when plotting my novels and ensuring that my characters and their actions do not stray too far from the realm of plausibility. But the ability to strip away the superfluous to reveal the meaningful is something I like to think I learned as part of my engineering education.

Wrapping it up…

I spent some time many years ago developing a theory about politics and how it can be explained using Newton’s laws and other engineering principles. I even expounded a bit on it in my first novel, The Best Laid Plans. (For those interested, the brief section starts on page 230 of the novel as Angus discusses with Daniel a speech he’s writing for an upcoming Engineering Society dinner.)

In The High Road, Angus also tells the story of the Canadian engineer’s iron ring as he presents his report and recommendations to the federal Cabinet on the collapse of Ottawa’s Alexandra Bridge. This short piece can be found on page 301 of The High Road.

So, as a young person, I embarked on what I thought would be a career in engineering. It didn’t turn out that way. But, for better or worse, I still view the world through an engineer’s lens, and that includes how I write my novels. I’ve come to believe that the engineering side of my brain is invaluable to my writing life. In fact, I wonder if I would ever have become a published writer without it.

In light of my own somewhat unusual engineering journey and where it has taken me, it was an honour—not to mention a shock—back in May of 2014 to receive McMaster’s Distinguished Engineering Alumni Award. As I noted in the video the university produced, it was brave of McMaster to recognize someone who has never even practiced engineering. But there you go. I was deeply honoured and humbled.

Many thanks for tuning in again this week and all the best for a happy and healthy 2023. See you next Sunday.

The bit about applying Newtonian physics to politics is insightful, but I also wonder whether you derive your comedy from the friction between engineering and human imperfection. The engineer expects everything he/she works with to obey the immutable laws of, for instance, physics, whereas human interactions, while we all sometimes wish they'd be governed by logic and predictable forces, are in fact messy and irrational. That point at which the behaviour departs from the physics is a comedic spark.

I mention this because, no matter how often I have tried to map out a precise outline for a literary project, I will quickly reach the point where one of my characters comes to life, puts his or her foot down and yells at me: "That's not how I intend to act!" And at that point the story takes off...

Although we marvelled at the concept of flight - mostly because of Superman - our summer days were spent building go-carts with wheels from prams to race down Mommaletti Hill. How many near-death experiences, you ask? 😉

I do so appreciate how you are able to present your very focussed and disciplined writing process, Terry. We couldn’t be more different in that. Referring to myself as a “chunk” writer, I find that I can’t ever really shut my ideas -brain down and just keep creating and recreating scenes and plots in my head constantly. These I write on sticky-notes, napkins, newspapers and my arms (when there is no paper around. I even leave notes on my cell. The real discipline comes in when I sit and write which happens for very long stretches of time. Days, sometimes.

Reading this was good for me. It made me question my own process which, I realized, was in action even while reading your blog. In fact, you gave me a great idea that I will explore! If it goes anywhere, I’ll be sure to give you credit!

Thanks again for a wonderful and insightful piece, Terry.