Trying to understand my Hemingway fixation

Writing Life: 19

The title of this post refers not to helping you, dear reader, understand my fascination with Hemingway, but helping me understand it. I can’t figure it out. For more than fifteen years now I’ve been deeply interested in the life of Ernest Hemingway—particularly his formative Paris years. I have quite a number of books on Hemingway. (Oh my gosh, it’s worse than I thought. I gathered as many of my Hemingway books as I could find and arrayed them on the floor of our third-floor library where I write. There ended up being more than two dozen—and that doesn’t include the many more e-books on Hemingway I have safe and secure on my iPad.)

And I’ve read them all. Why, you ask? Good question. I don’t have a straightforward response.

Hemingway the person? Nope.

(Warning #1: Hemingway fans will not like what follows.)

You see, despite my interest in Hemingway, I think he was a colossal jerk in almost every way throughout his eventful and troubled life. He was also a long-suffering alcoholic with the predictable consequences. Now it is clear in the last years of his life, he was living with mental illness that, despite treatment at the famed Mayo Clinic, worsened and culminated in his suicide at the age of 61 (two years younger than I am now!). His declining mental state clearly and tragically affected his behaviour in his final years.

So I don’t hold his late-in-life behaviour against him. He was unquestionably suffering and unwell in his last few years when he was administered 20 rounds of Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) at the Mayo Clinic, the standard treatment at the time. (An interesting book on the topic of his mental illness is Hemingway’s Brain by Andrew Farah, a leading American psychiatrist. Here’s a JFK Library Forum interview with the author.)

However, prior to his rapid mental decline in his late 50s and early 60s, he was unreasonably competitive, self-centred, and mean-spirited—particularly to those who had helped him, like the then famous writers Sherwood Anderson and F. Scott Fitzgerald. He was a serial adulterer who treated all four of his wives abominably. He held grudges for years over what were often only minor infractions and sometimes offences only he perceived.

He routinely, some would say constantly, embellished his exploits—simply put, he lied… a lot—starting at a very early age. This was perhaps first evident when he was only 18 years old in the ever-changing details of his admittedly horrific and heroic experience in the Great War when he was seriously injured from a mortar blast on the Italian front. It seems churlish to criticize him for his “recollections” of what was a near mortal injury when he behaved, by all accounts, bravely and selflessly in saving an injured Italian soldier. But Hemingway himself altered so many details of the story so often over the years, that the truth may well never be fully understood.

Hemingway the writer? Nope.

(Warning #2: Hemingway fans may like what follows even less.)

And now, let’s confront the elephant in the room. Of all the books I own about Hemingway, only three or four were actually written by him. Why? Well, despite many, many—and I do mean many—attempts, I just don’t like his writing. There, I said it. I understand and accept that he, perhaps more than any other writer of his time, revolutionized literature, eschewing the flowery even ponderous prose of the pre-war period in favour of stripped-down sentences that were spare and sparse. I suggest that most scholars the world over agree that he changed the literary landscape. I agree, too. He also developed what has come to be known as his iceberg theory of writing, where much of the story is not actually written, but is only implied. In other words, what we read is above the waterline, but much more of the story lies beneath the surface for the reader to figure out. I accept all of this.

My problem with Hemingway’s prose is likely rooted in the fact that—as I’ve said often—I hail from the “why use six words when twelve will do” school of writing. I love the richness and diversity of the English language. I like to splash around in it and explore its outer-reaches. I love a long, flowing, beautiful and carefully crafted sentence. So despite the high-stakes adventures Hemingway writes about—and believe me, I wish this weren’t true—I find them dull to read. In my mind, Hemingway often leaves a bit too much of the story below the waterline, and I lose interest. (Sad but true.) I know I’m not alone in this view, but I’m no doubt in the minority.

But I’m not a minority of one. John Irving is also not a Hemingway fan. I discovered this many years ago watching Irving in old TV interviews on YouTube, but it was long after I’d already made up my mind about Hemingway’s prose. Here’s what John Irving said recently in a great 2022 CBS interview (watch it here) and also in a 2012 Atlantic article (read it here).

My thoughts exactly! I was happy to learn of John Irving’s views on Hemingway and that I was not alone in this view.

So why read and write about him so much?

Another good question. Initially I wondered if it was because, after Shakespeare, Hemingway is probably the most iconic, the best known, the quintessential writer in our cultural consciousness. If a global poll were taken asking respondents to name the most famous writer of the last century, I suspect that Hemingway would lead the pack. My interest in Paris and expat writers seemed to coincide with writing my first novel and the joy I was experiencing discovering this new world. So maybe it was natural for me to gravitate to a big name like Hemingway?. No, I don’t think that’s why I became so interested in him.

More likely, I think, it was discovering Paris, not Hemingway, that may have triggered it. It’s no coincidence that I’m far more interested in Hemingway’s Paris years, when and where he was just finding his feet as a writer. It may well be that my interest in Hemingway’s early years is driven by my fascination with Paris in the 1920s—a nexus of cultural change—and Hemingway just happened to be there and loomed largest among his fellow expat writers. Hmmm, maybe I’m on to something. In fact, I have even more books about 1920s Paris than I do specifically about Hemingway.

So perhaps I’m confusing my interest in the City of Light with a Hemingway fascination. After all, I do write beneath a large, framed map of 1928 Paris and visit my favourite city every couple of years.

I have written about 1920s Paris, Hemingway, and the other expat writers in my novels, particularly my fourth novel, No Relation (read my post about it here). And in my upcoming ninth novel, A New Season (read my post about it here), the Paris of 2023 and the 1920s plays an important role. So perhaps I’m really interested in the Paris of a century ago and that means, by necessity, also reading about Hemingway. Yeah, let’s go with that, at least until a better theory presents itself. It may be the only logical reason to explain why I like reading about a (in)famous, Nobel Prize-winning writer, who was also, arguably, a misogynist, an antisemite, an egomaniac, an inveterate liar, and who also happens to write simple, declarative, and at the time, revolutionary prose, that still leaves me cold.

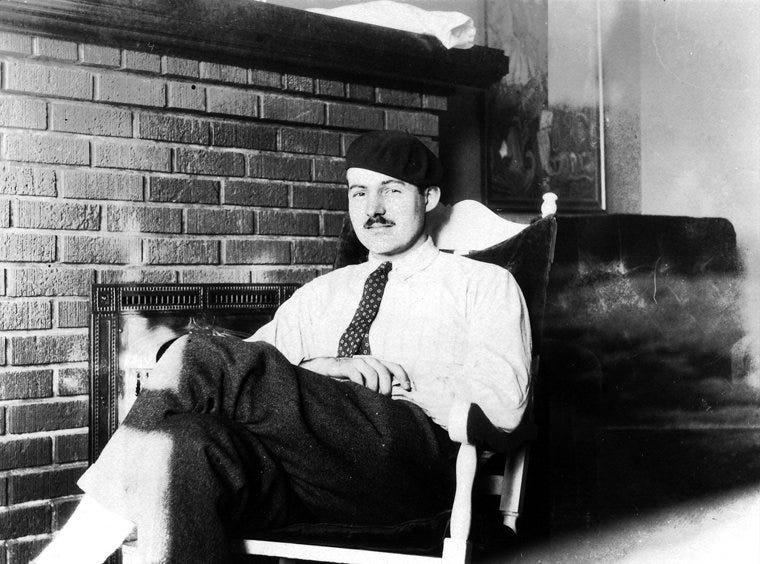

I even have a couple of photos of Hemingway on display in our library where I write. Sometimes I wonder if they’re on my wall as a reminder not to behave as he did.

Okay, that’s enough

I’m not really sure if I’m any closer to understanding why I find a writer I don’t like as a person, and who writes prose I don’t like, quite so fascinating, but there you go. Despite my misgivings, if a new Hemingway biography is released—and that happens every couple of years—I imagine I’ll read it, too.

By the way, for those of you interested in or enamoured of Ernest Hemingway, there’s also a podcast I listen to called One True Sentence (a line from A Moveable Feast).

On a related note, I’m now reading the published letters of his third wife, the amazing Martha Gellhorn, a war correspondent perhaps without peer.

I’m open to any of your theories explaining Hemingway’s hold on me. I’m coming around to the notion that it’s all wrapped up in my love for the history of Paris, and that we can still wander what are essentially the same streets and enjoy the same cafés as did Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Morley Callaghan, and the rest of them, all those years ago.

Thanks for stopping by. Feel free—and it is free—to subscribe if you haven’t already so you don’t miss future posts. Sharing this with others in your network is also greatly appreciated. Until next week…

I was always fascinated about his life, but like you had trouble getting beyond the first two chapters. I did not like the brief sentences, lack of richness in his prose. When I hear people rave about his books,I keep wondering what exactly I have missed. Hope you are thriving Terry?

Terry, A fun debate with yourself! Here's another new book for your collection. "Hemingway's Widow: The Life and Legacy of Mary Welsh Hemingway," by Timothy Christian. After reading about his life with Hadley (wife #1), I'm looking forward to reading about Mary (#4). I'm troubled by the way he treated women. I've already told you about my book, "Through Her Opera Glasses," based on my mother's letters from Paris 1930-1931. As you adore Paris so, you might enjoy her adventures.