(Warning: Self-indulgent reflection and emotional sharing ahead. If feeling nauseated, stop reading immediately. Likely of more interest to writers, but perhaps readers will find something, too.)

I’ve been thinking about this post for a very long time, never being certain that it would ever see the light of day. It feels almost like a confession—as if I’m about to lay bare my innermost thoughts about the welcome turn my life took nearly 18 years ago when I wrote my first novel. I’m not sure why I’ve been reluctant to share exactly how I feel about it all. It may be because my journey as a writer has not conformed to the traditional struggling artist narrative—you know, the writer who laboured for years with unread manuscripts gathering dust in a desk drawer and a wall filled with rejection slips. That wasn’t my experience—for which I’m grateful and perhaps a little embarrassed. It may be that my resistance to talking more openly about it is driven by guilt that I’ve been so lucky in my writerly life. There’s a line I’ve used often in my early book talks and still occasionally trot out. I’d say “I feel as if I’ve exhausted my lifetime allocation of good fortune—that I haven’t paid my dues as a writer.” It wasn’t hyperbole. I actually felt that way, and still do to a certain extent.

But it seems as if this is as good a time as any for me to exhume and examine those feelings (if only to understand them myself). Besides, this feels like a safe space for me to share with you what it means to me to be a working writer, for without all of you, and many, many others, I simply wouldn’t be.

What? You were 45 when you wrote your first novel?

As I think I’ve mentioned before, I came to writing later in life than do most writers. Yes, I was 45 when I wrote my first novel. By that stage, I was already 21 years into a career in which I was happy and successful. I was also very happily married—still am—with two sons and a mortgage. At that somewhat advanced age for a rookie writer, I think (and hope) I was able to bring a little more objectivity, perspective, and maturity to my fledgling foray into the writing world. I also had more of an inclination to consider how I was feeling. To observe, assess, and record the journey. (You can see that instinct in the early posts on my website/blog at terryfallis.com. I considered my site to be a digital scrapbook of sorts, for better or worse, capturing these new experiences I was pursuing as a writer.)

It was early 2005 when I started writing The Best Laid Plans. Without being too melodramatic about it all, I felt different—inside—almost immediately. I kept that to myself as I was still sorting through what it meant. All I can tell you is that I knew something was different long before that first manuscript was finished, long before it was greeted by a deafening silence from agents and publishers, long before I podcast and then self-published the novel, and long before that first self-published novel won the 2008 Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour. I’d been happy and successful in my public affairs/communications consulting career, but was surprised to discover that writing a novel made me even happier, even if success was still some distance off. I was surprised by the calm certainty that engulfed me. I had found what I felt, perhaps even what I knew, I was supposed to be doing. There was no empirical evidence to justify my newfound belief. I just knew how writing that manuscript made me feel.

Of course, I didn’t really tell anyone about how writing that first novel made me feel. I still thought of it as a self-indulgent fantasy. But, again, I knew how happy and content writing it made me. Don’t confuse this with belief in the novel itself. I had no idea whether I’d written a viable novel or not. I didn’t know if the story held together, or if the characters were believable, or if it was funny. I just knew how the exercise of conceiving and writing it made me feel inside. In short, it made me feel… whole.

I think about it constantly

From 2005, when I started that first manuscript, right up to this very minute, I have thought daily, sometimes hourly, about being a writer. Now that I’ve left my day job to write full-time, I still think about being a writer, almost constantly. I’ve never admitted that to anyone, but I confess it’s true. And that’s been happening for almost 18 years. That tells me I have in fact found what truly fulfills me (cue the violins and roll the credits).

But back to the early days, I was cleared-eyed enough to know—particularly given my utter inability (initially, at least) to interest an agent or publisher in my manuscript—that writing would have to remain a weekend endeavour and that I’d have to continue to work hard (and happily) at my day job. At the time, I was half-owner of a growing and successful communications agency with 40 employees and offices in Toronto and Ottawa. I had a responsibility to my co-founder, our clients, and our employees to keep my eye on the business ball. And so I did, for years and years—10 years before I wrote that first novel and another 17 years afterwards. Did I ever think of my writing life while at the office? Of course. Hard not to. But my obligations were clear. And I truly liked and respected my business partner and colleagues—still do. In the last few years of my time with the agency, I was on salary four days a week, leaving me a pool of 52 clear days a year to devote to all the book talks, festival appearances, and other touring I was doing. That made my writing life so much easier.

Then it was all in the open

As I’ve written before in this space, winning the 2008 Leacock Medal was, in a way, my literary coming out party. It, coupled with winning CBC’s Canada Reads a few years later, profoundly changed my life as a writer and allowed me to skip what are usually the early difficult years that even our best writers endure before breaking through. (I know this video clip was included in an earlier post, but this literally captures the very moment when my dream of being a writer seemed to come true, if only in my mind.)

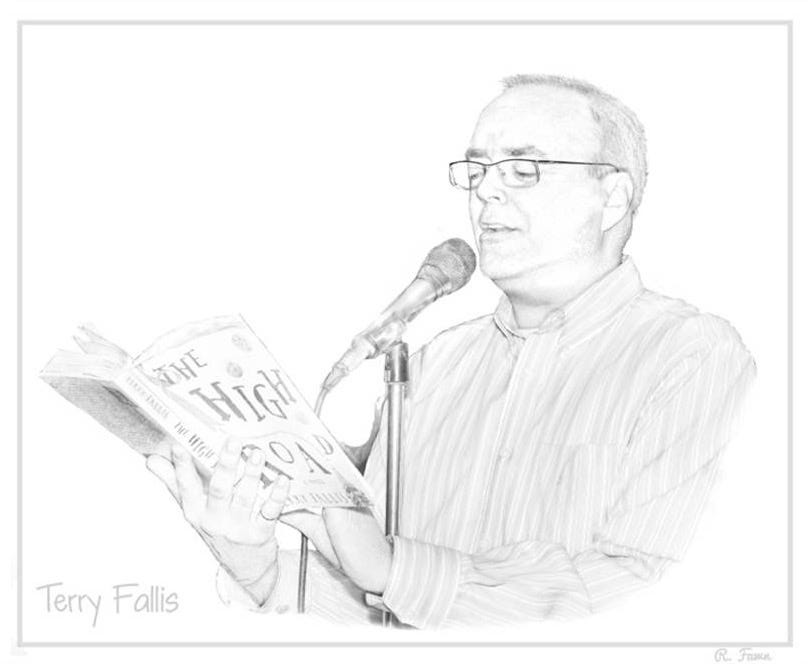

Shortly thereafter, thanks to winning the Leacock Medal, I was invited to do my very first reading at a People for Education benefit at Soulpepper Theatre in Toronto. I’ve done more than a thousand talks and readings in the years since, but it all started with what I will always think of as my “Leacock shock.”

There is not a more grateful writer in the world than I. For more than 15 years I’ve been pinching myself every 20 minutes or so. I know I’m very lucky. Sure, I worked very hard at it and still do. But I also know I’ve been very fortunate and never let myself believe my own clippings. I always want to be the same person who wrote that first novel when no one was watching.

Feeling like a writer and its side-effects

Part of becoming a writer later in life is that I find myself doing things that make me feel more like a writer—as if I’m making up for lost time. I know I am a writer, but it seems I also like the more superficial accoutrements that I associate with being a writer. I know it seems almost childish, but there you are. I remember getting my first hockey jersey when my twin brother, Tim, and I were nine years old and began our less than stellar hockey careers—that continue to this day, I might add, though still less than stellar. That first jersey with my favourite number 10 on the back, didn’t make me a better hockey player, but it did make me “feel” like a hockey player—like I belonged. The same is so in my writing life, though you might think my age would make such material things unimportant. Nope.

When my first novel was published, I searched for, and finally found a set of typewriter bookends that I still love. My own novels now stand between them. At an antique market, I bought an old and seized Underwood typewriter just because it felt writerly.

For Christmas one year, I asked for and received the framed 1928 map of Paris that hangs above my writing desk—an homage to the expat writers of that time and place. I later ordered online a framed print of an old typewriter that hangs on the same wall. Again, I don’t really know why. It just meant something to me and made me feel a part of something.

There are also framed photos of Hemingway and Robertson Davies hanging in our library where I write.

If that’s not enough, I have two Paris Review sweatshirts and a T-shirt featuring a QWERTY keyboard. (Yes, I got the T-shirt!) I even found—made using antique typewriter keys—cufflinks (T&F) and a lapel pin (T) that I sometimes wear at writerly events. They’re just cheap little trinkets, but they have meaning to me. (I know, I know. It’s silly. It’s like I’m twelve years old collecting hockey cards. In my defence, I came late to the writing party.)

I know what you’re thinking. How juvenile to succumb to these materialistic, superficial, giddy urges. (I know. I feel the same way. But there you are.) I’m a little embarrassed to admit I’ve acquired this writerly miscellany. You might expect it from a very young writer, but I’m about to turn 63! It’s hard to fathom, even though I’m the only one who sees most of these little writerly indulgences. All I can say is that being a writer is so important to me I want to be surrounded by things that make me feel like a writer. I want to immerse myself in the writing life—not just to be a writer, but to feel like a writer. And these things, yes even a paltry lapel pin made out of an antique typewriter key, give me some little shot of inspiration and remind me that I’m a member in good standing of the ancient and sometimes respected guild of writers and storytellers.

Of course, I also collect books about writers and their approach to the craft. They inspire me, too. And not just the expat writers in 1920s Paris.

It actually makes me all verklempt

Few people truly understand just how important my writing life is to me—I guess at least until this post goes public. I’ve kept it pretty much to myself, unless specifically asked. I feel sensitive about it so I try to be cool—you know, like it’s no big deal. But that’s a lie. It’s a big deal to me.

I may have written about the movie Broadcast News before, so forgive me if I’m repeating myself. But there’s a great scene when the somewhat vapid and vacant but handsome news anchor, played wonderfully by William Hurt, asks the smart but “never destined for primetime” reporter Albert Brooks, “What do you do when your life exceeds all your expectations?” The Albert Brooks character replies, “You shut up about it.” Funny line, but I think it’s why I don’t talk much about my feelings about my writing life. Some days, I still can’t believe my good fortune. So “I shut up about it.”

My wife has always known my writing life is important to me and has always been very supportive. But even she may not have fully realized what it means to me. One night, about a year ago now, when she agreed it was time I left my day job so I could write full-time, I promptly burst into tears. I didn’t mean to. I just did. Let’s just say she wasn’t expecting quite so emotional a reaction. Even as I write about this important memory I can feel the lump forming in my throat.

Enough already, wrap it up

To this day, when I’m introduced at festivals or other book events, mention is always made of the so-called “successes and awards” that have somehow—miraculously, to me—come my way. That always makes me a little uncomfortable, but it’s part of the marketing and promotion that helps sell books. I get it. But what always thrills me, more than anything else, is just to be called “a writer,” and to feel like a writer. Being, and feeling like, a writer, is everything.

Thanks for letting me dig through the emotional entrails of my writing life. It’s been quite a ride with more to come. Consider subscribing if you haven’t already and we’ll see you next week.

Nothing self-indulgent about this one. Loved it. (Especially the "My wife has always known my writing life is important to me..." paragraph!)

Thanks for sharing this perspective of what being a writer means to you. It cuts through the challenges of character and plot development, word counts, and cover designs and speaks to the meat and potatos of writing, the part that keeps me coming to the table and pushing through what’s before me. I feel the same about not talking about how fortunate I am to be able to do this at my will at this time of my life. We are blessed.